chronicles

Posted by Farmer Nik

0 Comments

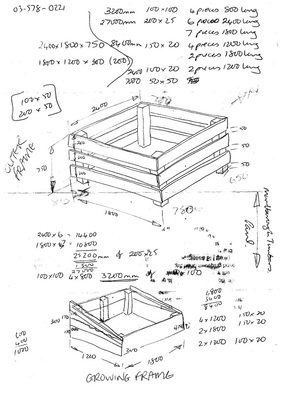

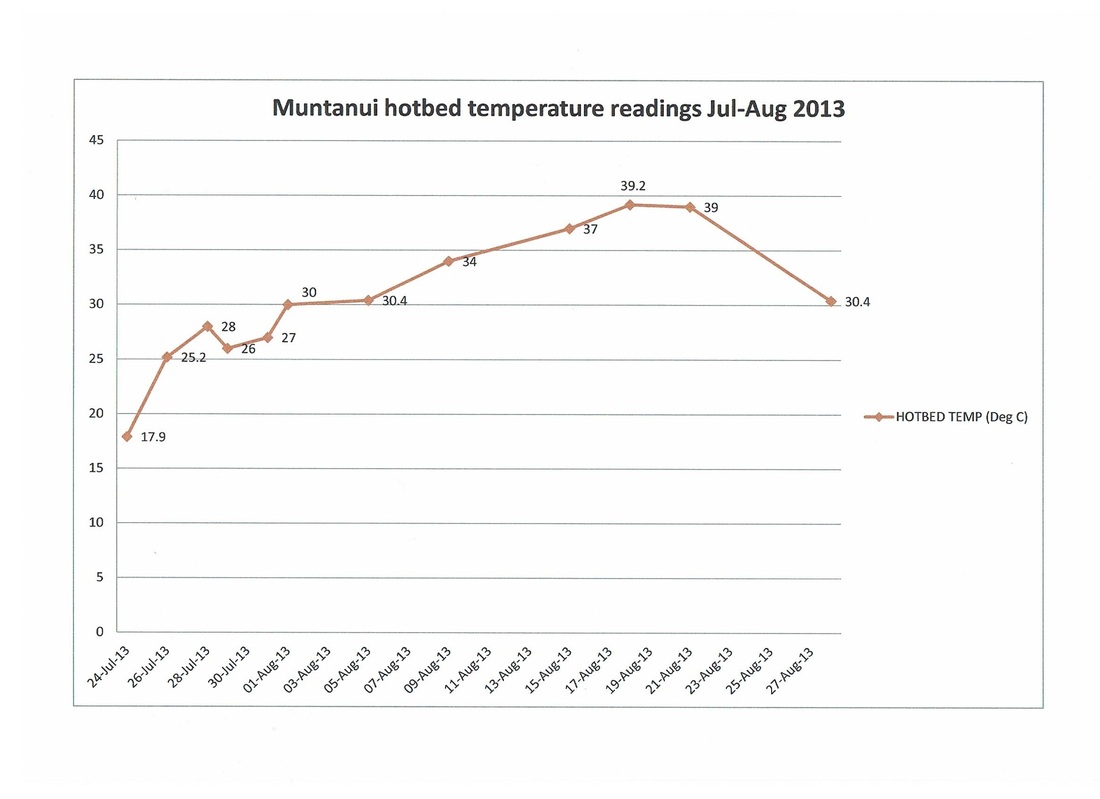

There are many different kinds of "hot beds" in the world and all sorts of instructions for "making" them but here I'm talking about using the heat generated by a compost heap to germinate seeds and grow plants very early in the season. Sorry. France: a hotbed of horticultural excellence I first read about hotbeds in The Winter Harvest Handbook by American organic market gardening guru, Eliot Coleman. He referred to the incredible 19th century market gardeners around Paris who used hotbeds to supply the city with fresh vegetables and fruit all year round These growers also exported vast quantities of produce over the pond to Britain. Each market garden was usually no bigger than one or two acres but they were very intensively cultivated and extremely productive. I filed this information away in the back of my head until the NZ Biodynamic Conference back in May, where I spotted Hot Beds, a great little book by British horticulturalist and hotbed expert, Jack First. There are detailed instructions in the book on how to construct, fill and maintain hotbeds and I thought I'd like to give it a try. (Translation: I bullied Farmer Wan into making one for me.)  Step-by-step instructions on how to build a hotbed 1. Build the outer frame The bigger the outer frame, the more raw material it will hold and the longer the hotbed will stay warm. Farmer Wan made ours from untreated eucalyptus, 2400mm long (the sun-facing side) by 1800mm deep (or 8 ft long by 6 ft deep). The height varied at each corner because the land was sloping but on flat ground, it would be 750mm (approx. 2 ft 5in). 2. Fill the outer frame to the top with manure mixed with straw Horse stable sweepings are best for this because horses produce copious amounts of nitrogen-rich urine, which is great for getting the composting process started. We settled for red clover straw, cow manure and Farmer Wan peeing on the heap whenever he felt the urge. 3. Build the growing frame This should fit comfortably inside the outer frame with room to spare. Farmer Wan made ours 1800mm long by 1200mm deep (6 ft by 4 ft). As you can see, it slopes. This prevents seedlings from being shaded out.  4. Make the lights These cover the growing frame and keep in the heat. They should extend just past the growing frame so that rain runs off and doesn't flood the seedlings. Farmer Wan made three separate, lightweight frames. Traditionally, these were covered with glass but he used polytunnel plastic to cover ours. 5. Fill the growing frame with growing medium We used a soil/compost mix with good drainage. 6. Monitor the temperature of the hotbed This was a good excuse to buy a great new gadget -- a digital thermometer with a metre-long probe. The hotbed temperature should be stable or starting to decrease before it's sown with seed. For the first couple of weeks, we took temperature readings every two or three days but we slackened off towards the end. It took a while for the bed to get cranking but at peak, it reached just under 40degC -- more than 20 degrees higher than the ambient temperature. 7. Sow seeds On 19 August, I made shallow furrows in the growing medium and filled them with seed-raising mix. I sowed three rows of lettuce, a row of English spinach and a row of corn salad (a.k.a. lamb's lettuce). On 24 August, I sowed four rows of a carrot/radish mix. 8. Water and cover with lights Once the seedlings are up, they need adequate ventilation. The lights should be raised on calm, sunny days to provide airflow, and replaced before the temperature starts to drop in the afternoon. I'll give you a progress update soon. Posted by Farmer Nik  Bantman and Robyn, a perfect Pekin pair Bantman and Robyn, a perfect Pekin pair The second anniversary of our permanent move to Muntanui quietly slipped by last Wednesday. It rained. Farmer Wan worked on our sheep yards and I spent the day inside, writing. Because there's always so much to do here, we're always looking ahead. We don't often take the opportunity to reflect on what we've already done. Usually, that's done for us by people who have visited more than once and remarked on the changes. Our biggest struggle so far hasn't been our ignorance of farming -- that tends to sort itself out whether you want it to or not. Stuff happens and you deal with it and the outcome isn't always good, so you work out how to prevent it from happening again or how to handle it better if it does. The farm shows us what our priorities need to be and we just get on with it. No, our biggest struggle over the last two years has been learning to work with each other. That, for me, was a huge surprise. I thought we'd be great -- some kind of super-team, charging implacably, successfully, from one farming challenge to the next. Nah. Not even close. In reality, we've probably fought more over the last two years than in the previous 12 years combined. Neither of us likes being told what to do -- at least, not by each other. We think differently. We approach things differently. We have different levels of energy, stamina and patience. It's a wonder we haven't strung each other up. But when we're trying to solve a problem and we're on the same frequency and it's working -- ahh. It's magic. Until one of us tells the other what they should do next. So it's a work in progress. Muntanui itself continues to delight us. We both love this place so much and we have no regrets about moving here. We're firmly embedded in the local community, now. We've learnt a bit about farming and livestock and, once we get some remaining infrastructure sorted out and a bit more experience under our belts, we'll be better equipped to roll with the punches. We're not kidding ourselves that it will get easier (one word: weather) but we'll at least have the basics in place. Some of the stuff on our To Do list from two years ago still hasn't been started, and we've done a lot that was never on the list in the first place. In our third year, we're getting serious about both renewing our pasture and practising livestock husbandry. We'll be making more changes to the landscape and should also be a lot closer to feeding ourselves. There might even be some surplus to sell. So plenty to be getting on with, then. Lucky that we love work -- and each other! Posted by Farmer Nik |

About Ewan and NikiFarmer WanScottish mechanical engineer with a deep and abiding passion for good food. Outstanding cook. Builder of lots of stuff. Cattle whisperer. Connoisseur of beer. A lover rather than a fighter. Farmer NikKiwi writer and broadcaster who hates cabbage, even though she knows it's good for her. Chook wrangler. Grower of food and flowers. Maker of fine preserves. Lover of dancing and wine. Definitely a fighter. Archives

November 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed